Gender sensitive medical devices are another step towards a more inclusive and attentive to the patient’s needs healthcare. This new challenge has taken its first steps in recent years and is gradually establishing itself, especially starting from the United States. But there is still a long way to go.

Now more than ever, we need to understand the implication these attributes present for the performance of medical devices in both women and men, particularly as medical devices play an increasingly prominent role in providing health care

Health of Women Program Strategic Plan 2019 FDA

Kathleen Sheekey, a retired executive, lives in Washington and loves to travel. Just during a trip she noticed how much the pain that she had felt for some time in the middle of the leg, between thigh and calf, was limiting her. “I was walking around and couldn’t wait to get to the next bench,” she recalls. As the trouble worsened, she found it more and more frequent to resort to pain relievers and bandages. Until knee replacement surgery became inevitable. It was 2007 and she was one of the first patients to receive a specific prosthesis for women.

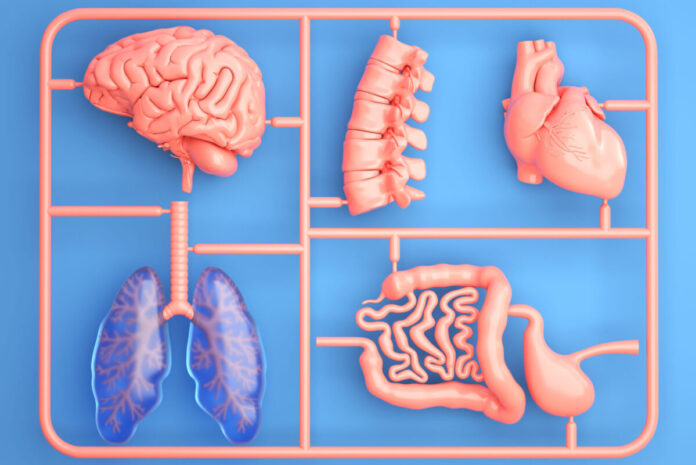

Taking gender diversity into account

To date, there are numerous manufacturers who build systems of this type, making use of computer-assisted projects and the most innovative technologies. The declared goal is to “trace the patient’s joint as closely as possible, ensuring better functionality, longer life, and reduction in the risk of complications”. In fact, there is some difference between a male and a female knee. In size, first of all, since a woman’s knees are smaller than a man’s. And also in the anatomy, with differences concerning both the Q angle, formed between the quadriceps muscle and the patellar tendon, and the distal part of the femur, which articulates with tibia and rotula.

But does taking these differences into account in the design of implants bring real benefits to the patient? The debate is ongoing, with studies reaching conclusions that are not always unambiguous.

A research published in 2010 in The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery and carried out by experts from the Athens Orthopedic Clinic had, for example, found that the protrusion of the distal femoral component in standard prostheses implanted in women is about three millimeters, which would double the odds of local pain two years after arthroplasty. On the other hand, a study published in 2014 in Knee Surgery & Related Research and carried out by Korean researchers showed that gender-sensitive prostheses that reduce femoral protrusion do not actually provide any measurable benefit three to four years after surgery. These results were confirmed by a systematic review published in 2020 in Sicot-J, the journal of the Société internationale deirurgie orthopédique et de traumatologie, and conducted by French researchers. The review notes that “further research needs to be performed to further define the role of gender-specific implants”.

Gender sensitive medical devices: ongoing research

The “female” knee prosthesis is one of the best known examples of so-called gender sensitive devices. They are designed and built specifically for women, taking into account the needs, characteristics and peculiarities that differentiate them from men. In the orthopedic field, another joint under the lens from this point of view is that of the hip.

Jama Internal Medicine published in 2013 a study carried out by researchers at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York on over 35,000 hip surgery patients in 46 hospitals. The study found that, after three years, women were almost 30% more likely than men to undergo a revision of the surgery. This is mainly due to dislocations and wear of the prosthesis. “Women have a different pelvic and hip anatomy than men, as well as have greater bone loss,” said Art Sedrakyan, co-author of the study. “However, since the overall risk of recurrence has remained low, it is premature to argue that they need specific prostheses”. To date, the last word has not yet been said and further research is underway.

A female heart

Nemah Kahala, a woman with advanced heart disease, came to UCLA Health Center in Los Angeles in 2015. She was in really bad condition upon arrival. Her heart pumped little more than a trickle of blood and she urgently needed a transplant. Patients with these conditions are usually equipped with a ventricular assist device for a few weeks. It is a mechanical pump known as an artificial heart, which replaces the ventricular function with the aim of increasing the amount of blood circulating while waiting for an organ to become available (“bridge” to transplantation).

But in Nemah’s case there was a problem. The woman was small and short in stature and at the time the only device approved by the FDA (the 70 cubic centimeter one) was too big for her. So the doctors had to make a special request to the competent authorities to be able to use a smaller heart, of 50 cubic centimeters. The derogation was granted to them and the therapeutic path could continue.

The standard device had received the green light from the US agency in 2004. Instead, the smaller one, suitable for most women, landed on the market many years later. The regulatory body only approved it in March 2020. A wait of 16 years, probably motivated by the fact that 80% of the people who need an artificial heart are men and 20% women. The 70 cubic centimeter device is implanted in 88% of cases in the former and only in 12% in the latter.

More trials on women

To the aspects concerning the suitability and functionality of gender sensitive medical devices are added those related to safety. Also in 2015 and still on the subject of “artificial heart”, a study conducted by experts from the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia was published in The Journal of heart and lung transplantation. Well, according to the researchers, women using the continuous-flow left ventricular assist device while awaiting transplantation are at greater risk of stroke than men. “More research is needed to fully understand these differences and whether device management strategies need to be tailored based on gender”, the authors conclude.

There seems to be some safety problem also on the materials front. The example of mesh systems, often made of polypropylene, is striking. They are used in urogynecological surgery for the transvaginal treatment of incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women. Already between 2008 and 2011 both the Food and Drug Administration and Health Canada, the Canadian government agency, had issued various warnings after thousands of women reported pain, infection, bleeding, urinary problems, nerve and tissue damage in following the implant. In the following years, many such products were withdrawn from the market and some cases ended up in court. In 2017, researchers from the Oxford University Centre for Evidence-based Medicine published a study in the British Medical Journal. They found that such networks had not undergone clinical trials in women before they were approved.

The problem was and is that, similarly to what happens with drugs, the number of women included in the trials on the devices is very small.

Breast implants and implantable contraceptives

A couple of years later, in 2019, the International consortium of investigative journalists started from the observation that women tolerate the implantation of metal-containing devices less than men. It therefore carried out a gender-oriented survey on the safety of devices. In particular, the journalists analyzed the Manufacturer and user facility device experience (Maude). This is the FDA register where reports of adverse events concerning these products are recorded. Over 340,000 cases of injuries or deaths were examined. Of these, 67% concerned women and 33% men: a disproportion that deserves to be investigated.

Lo sostiene anche la democratica Rosa DeLauro, che ha invitato l’ente regolatorio a «rafforzare la supervisione dei dispositivi medici in un’ottica di genere». DeLauro ha prestato particolare attenzione alla sicurezza dei device femminili. Tra questi ci sono per esempio le protesi mammarie testurizzate, accusate di essere correlate all’insorgenza del linfoma. C’è anche Essure, un contraccettivo impiantabile permanente recentemente ritirato dal mercato con l’accusa di provocare dolore, emorragie, perforazioni delle pareti uterine e delle tube di Falloppio. In seguito a queste sollecitazioni, l’agenzia ha assicurato che avrebbe intrapreso specifiche azioni, tra cui audizioni pubbliche e nuovi programmi di ricerca, per valutare e monitorare l’impiego di dispositivi nelle donne.

Democrat Rosa DeLauro also supports this, calling on the regulatory body to “strengthen the supervision of medical devices from a gender perspective“. DeLauro paid particular attention to the safety of female devices. Among these are, for example, textured breast implants, accused of being related to the onset of lymphoma. There is also Essure, a permanent implantable contraceptive recently withdrawn from the market accused of causing pain, bleeding, perforation of the uterine walls and fallopian tubes. Following these requests, the agency assured that it would undertake specific actions, including public hearings and new research programs, to evaluate and monitor the use of devices in women.

Towards gender sensitive medical devices

“Having information about sex is very important,” confirmed Diana Zuckerman, president of the National Center for Health Research in Washington and an expert in medical devices, “because some products differ in safety between men and women”. In April 2020, the FDA’s Center for devices and radiological health launched the Health of women project to promote the innovation of “female” devices. ““Every cell is sexed and every person is gendered,” said the director of the initiative Terri Cornelison. “Exploring and understanding unique issues related to the performance of medical devices in women is critical to protecting and promoting the health of all women.”

But how did the stories of Kathleen Sheekey and Nemah Kahala end? The first, after knee surgery, went back to walking painlessly, going up and down stairs, even playing tennis. The second of her received a brand new heart from a donor, which still beats in her chest today.

And in Italy?

With regard to medical devices “in pink”, it seems that something is also moving in our country. The Plan for the application and dissemination of gender-specific healthcare, adopted by the decree of 13 June 2019, dedicated a short paragraph to the topic. “A use of medical devices that takes into account the anatomical-functional differences linked to gender is not yet sufficiently considered”, the document reads, “even though it has been recognized as relevant in the health sector”.

An importance also reaffirmed by Fernanda Gellona, general manager of Confindustria medical devices:

Giving greater focus to the patient, identifying gender peculiarities, is considered essential by medical device companies, which have always been oriented towards personalizing devices. Today more than ever it is important, indeed indispensable, to take into account the many differences between men and women for greater appropriateness of care and a better allocation of resources.

In short, on paper the conditions for going in the direction of “gender sensitive medical devices” seem to be all there. Now we need to move from theory to practice.